The Strippers, Trump, and JD Vance

On No Kings Day I've been reminded of a famous meme...

As a Cambridge graduate, I’m often asked whether I think the so-called Oxford comma at the end of some sentences is strictly necessary. People assume that I must be against it purely out of loyalty to my alma mater. Nothing could be further from the truth; I’m actually a big fan (read to the end to find out why).

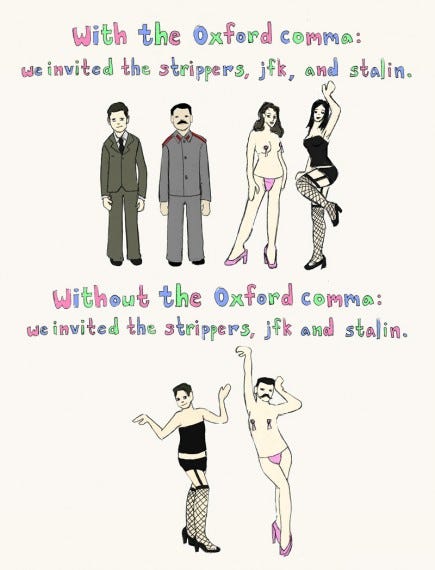

There’s a well-known cartoon that often surfaces on social media to illustrate the usefulness of this much-maligned punctuation mark. It shows two sets of party guests and invites us to distinguish between ‘the strippers, JFK, and Stalin’ and ‘the strippers, JFK and Stalin’. Even if you’ve seen it before, why not take a moment to refresh your memory?

Now, this cartoon works not because of the terrible drawing (to my mind, Stalin looks more like Freddie Mercury) but because of the humour caused by the difference between what was intended and what was written.

In the top example, the ‘Oxford comma’ does its work and separates Stalin and JFK from the strippers. They are clearly denoted as three separate entities. In the second example the absence of the final comma ‘pairs’ JFK and Stalin together and seems to place them in what we call grammatical apposition: rather than being separate from the strippers, they ARE the strippers.

Actually, since both scenarios are equally implausible, that extra comma is precisely how you might choose to differentiate the two possible outcomes. But there’s actually nothing wrong with it. In fact in the top example the ‘Oxford comma’ genuinely helps us to understand that there were four guests rather than two.

So while the meme may be famous, it doesn’t really solve the question ‘Is the Oxford comma strictly necessary?’

I was reminded of it when, in today’s Guardian, I came across the following sentence from journalist Robert Mackey reporting on a ‘No Kings’ rally in Portland:

“I just witnessed a remarkable scene further back in the crowd, as protesters carrying handmade signs passed a trio of street performers, dressed as Donald Trump, whose head was entirely constructed of Cheetos, JD Vance and Kristi Noem.”

The pleasing ambiguity of that image—the president’s head constructed out of JD Vance and Kristi Noem—could be attributed to the sloppy use of commas. But again it’s not really an ‘Oxford comma’ problem; rather it’s the result of what linguists call ‘rebracketing’.

Allow me to explain by breaking it down:

The object of the sentence (i.e. what I witnessed) is a trio of street performers. So far, so good.

There then follows a modifying clause describing those performers: dressed as Donald Trump… JD Vance and Kristi Noem.

But hidden within, there is also a relative clause describing Trump:

whose head was entirely constructed of Cheetos

Commas (whether Oxfordian or not) are used to separate items in a list. But they can also be used—usually in pairs—as an alternative to parentheses. So let’s try using brackets instead. We now have either

dressed as Donald Trump (whose head was entirely constructed of Cheetos), JD Vance and Kristi Noem

or

dressed as Donald Trump (whose head was entirely constructed of Cheetos, JD Vance and Kristi Noem)

Which information did the writer intend us to see? Presumably the former, but in the end it doesn’t much matter. Both images are appropriately bizarre and achieve their effect: the street performers and Mr Mackey have done us all a service and given us a laugh.

It’s worth pointing out that even if you add an Oxford comma in that sentence between JD Vance, and Kristi Noem, it still doesn’t solve the essential ambiguity. My advice to Mr Mackey would be to reorganize the whole sentence thus:

“I just witnessed a remarkable scene further back in the crowd, as protesters carrying handmade signs passed a trio of street performers, dressed as JD Vance, Kristi Noem, and Donald Trump (whose head was entirely constructed of Cheetos).

Why I’m in favour

From the above examples, we can see how commas help to avoid ambiguity, and in these cases there is no real cause for dispute.

But critics of the ‘Oxford comma’ complain that all final commas are redundant or useless. I happen not to agree.

Take a simple example:

“The causes of the war were many: territorial disputes, a failing economy, corruption, and poor leadership”

Now, it’s true in this case (as in many such lists) that the final comma before ‘and poor’ can safely be omitted. Have a go. It means the same with or without. But this is not an argument for dropping it.

To my mind the extra comma clarifies that there were four independent causes. To miss out the comma after ‘corruption’ has the effect of merging it with ‘poor leadership’ in a way that may not be true or intentional, so the final comma here acts as an aid to our logical understanding, as well as improving the rhythmical structure of the sentence.

That’s all on this topic for now. If you enjoy these posts, please consider subscribing or sharing.

Couldn't agree more. Imagine the parsing errors if an LLM missed that commma!