"Find the beef, the beer, the bread. Then look behind"

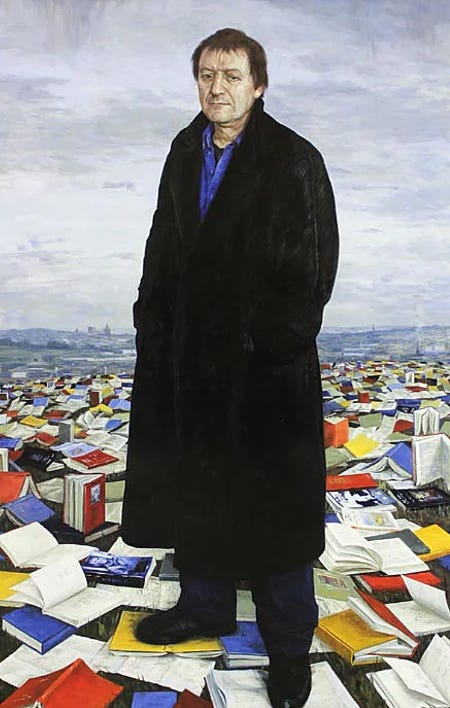

RIP poet and playwright Tony Harrison

My poetry bookshelves are particularly rich in the H department. Here reside the collected works of four great twentieth-century poets, one Irish (Seamus Heaney) and three associated with the midlands and north of England: Geoffrey Hill, born in Bromsgrove, who worked for many years at the University of Leeds before moving to Cambridge, where I was fortunate enough to be taught by him. Ted Hughes, from Yorkshire, whose strong, muscular verse made the natural world come powerfully alive—and who was appointed Poet Laureate on the death of John Betjeman. And Tony Harrison, also from Leeds, whose powerful poems and verse dramas combined a classical education with an uncompromising fealty to his Northern roots.

Of the four, Harrison was the most overtly political; his writing focused on his own sense of guilt at having left behind his working-class roots to go to university. Here’s his extended sonnet ‘Book Ends’, in which he recalls an awkward visit to his recently-widowed father:

Baked the day she suddenly dropped dead

we chew it slowly that last apple pie.Shocked into sleeplessness you’re scared of bed.

We never could talk much, and now don’t try.You’re like book ends, the pair of you, she’d say,

Hog that grate, say nothing, sit, sleep, stare...The ‘scholar’ me, you, worn out on poor pay,

only our silence made us seem a pair.Not as good for staring in, blue gas,

too regular each bud, each yellow spike.A night you need my company to pass

and she not here to tell us we’re alike!Your life’s all shattered into smithereens.

Back in our silences and sullen looks,

for all the Scotch we drink, what’s still between ‘s

not the thirty or so years, but books, books, books.

(Book Ends I, 1978)

The ingredients of that poem—the apple pie, the remembered grate of the old coal fire, and its modern gas replacement—perfectly capture the front room of the small terraced house in Holbeck where Harrison grew up. But the apostrophized ‘scholar’ picks up the complexity of his own and his father’s feelings about Harrison’s departure from his working-class origins, as does the final line—a conscious echo of Hamlet’s ‘words, words, words’ (which the elderly Polonius can never understand).

Here’s a less well known poem on the same theme. By the way, ‘snap’ is a northern dialect word for a packed lunch, in this case made up of last night’s ‘tea’ (evening meal):

Ah, the proved advantages of scholarship!

Whereas his dad took cold tea for his snap,

he slaves at nuances, knows at just one sip

Château Lafite from Château Neuf du Pape.

(Social Mobility, 1975)

The form of the poem—the witty epigram—is a bit of fun for a poet at that time immersing himself in 4th-century Greek verse. But the content absolutely betrays the feeling of the scholar’s fraudulence, of superficiality, of what we might call ‘impostor syndrome’. And the anglo-saxon monosyllables of his dad’s honest and meagre fare perfectly contrast the accented gallicisms of the wine labels.

Harrison’s greatest achievement is the long-form elegy ‘V’ - one of several poems inspired by Thomas Gray’s Elegy in a Country Churchyard of 1750. In Harrison’s poem, ‘V’ alludes to what he calls ‘all the versuses of life’

…from LEEDS v. DERBY, Black/White

and (as I’ve known to my cost) man v. wife,

Communist v. Fascist, Left v. Right,

class v. class as bitter as before,

the unending violence of US and THEM,

personified in 1984

by Coal Board MacGregor and the NUM”

The poem includes an extended dialogue between Harrison and a skinhead who spends his fruitless days descrating the gravestones on Holbeck Hill, including that of Harrison’s own parents and grandparents—working-class folk who produced beer, meat and baked goods for the local community.

In repeating the lad’s obscene graffiti, Harrison’s poem became instantly recognizable and hugely controversial for its use of profanities. Calls from a number of Conservative MPs to suspend its 1987 television broadcast only guaranteed it a substantial audience. You can still find the poem in its original published form here in the London Review of Books. It remains required reading for anyone investigating the state of Thatcher’s Britain during the miners’ strike.

Tony Harrison died today. In ‘V’ he muses that one day he will come to lie in that same family grave. He jokingly remarks that as a poet he won’t be short of company: after all, an organ-builder called Wordsworth and a leather-tanner called Byron lie in adjacent plots. But despite his years of scholarship, his volumes of poetry and dozens of plays for the National Theatre, it is with his working-class forebears that he most associates:

If, having come this far, somebody reads

these verses, and he/she wants to understand,

face this grave on Beeston Hill, your back to Leeds,

and read the chiselled epitaph I’ve planned:Beneath your feet’s a poet, then a pit.

Poetry supporter, if you’re here to find

how poems can grow from (beat you to it!) SHIT

find the beef, the beer, the bread, then look behind.

(‘V’, 1985)